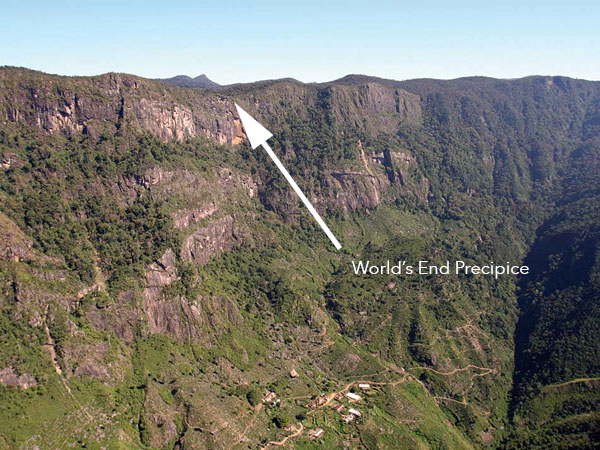

Horton Plains is home to a spectacular 12km hike through Sri Lanka's only Cloud Forest national park. For the uninitiated, the two big attractions here are World's End—a sheer cliff with an 870m drop—and Baker's Falls, a 20m waterfall named after the 18th Century explorer Samuel Baker.

An aerial photograph of the World's End precipice. The mountain in the background above and to the left of the arrow is Kirigalpota, which you can also access via Horton Plains

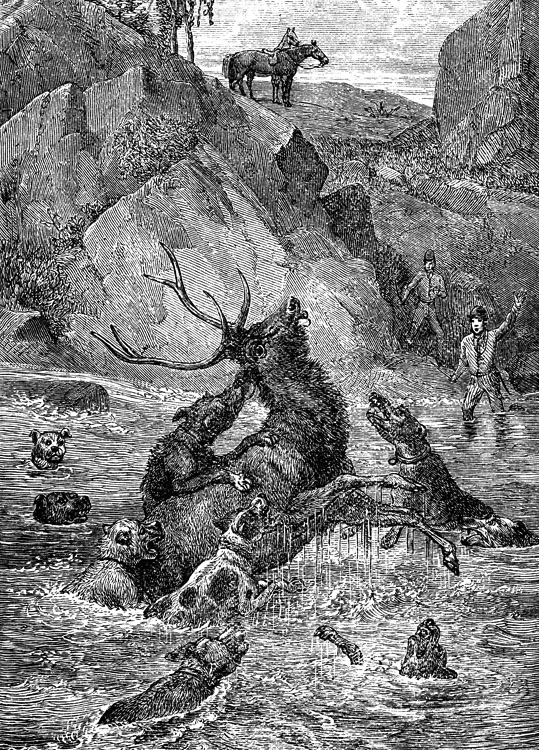

Baker's Falls, discovered by Samuel Baker in the midst of a sambar hunt in the 1800s. Our audioguide contains a reenactment of Baker's own rather harrowing telling of the story

While most tourists visit to see just those two things, there's a lot more to it than that. Horton Plains is home to heaps of endemic species of plants and animals regularly seen here and found nowhere outside the cloud forests of Sri Lanka. This ecosystem is one of the rarest and most vulnerable in existence today.

I've worked with Rohan Pethiyagoda and an entire team of zoologists, cartographers, photographers, archeologists and voice actors to assemble what we think is the missing audioguide to Horton Plains. In it you'll hear about all this and much more, including a few short lessons on animal behaviour, ecology and geology, and of course some girl-guide/boy-scout stuff like how to identify birds and frogs by just their calls.

As you can probably tell, I'm pretty enthusiastic about this. If you'd just like a hike, Horton Plains and this audioguide probably aren't for you (Ella's probably more your style). But for everyone else, I think it'd be a shame to visit the plains without it.

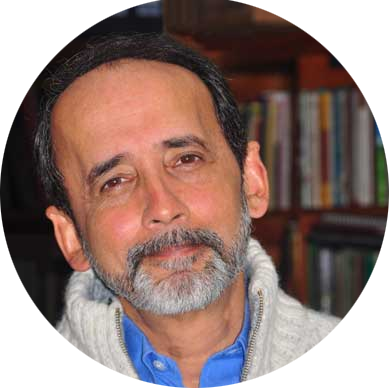

About the expert

Rohan Pethiyagoda is one of Sri Lanka's best-known biodiversity scientists, mostly because over the last 30 years he and his colleagues are responsible for the discovery of almost 150 new species of animals from Sri Lanka (a few of which are endemic to Horton Plains).

If have your finger on the pulse of the biodiversity community some of Rohan's roles and accomplishments are probably familiar to you: He was elected deputy chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission, he's published about 60 papers in scientific journals (including a few in Nature and Science) and he currently serves as editor of Asian Freshwater Fishes for Zootaxa. That said, if you've seen Rohan in the news before it's probably because he named an entire genus of fish after Richard Dawkins in 2012 which, for reasons we still don't understand today, made a bit of a splash in the British media.

Rohan's written quite a few books on the biodiversity and natural history of Sri Lanka, including "Horton Plains: Sri Lanka's Cloud Forest National Park", which is generally considered the definitive guide to Horton Plains. For this park, there's probably no better person in the world to be your guide.

All AudioLanka guides feature:

Offline Access

All guides work offline. Download them before you head to your destination via a secure in-app purchase and you're all set

Curated Audio

Produced and narrated by local and international researchers, academics and domain experts

Offline Maps

High-quality, bespoke offline maps and imagery by field guides and award-winning photographers